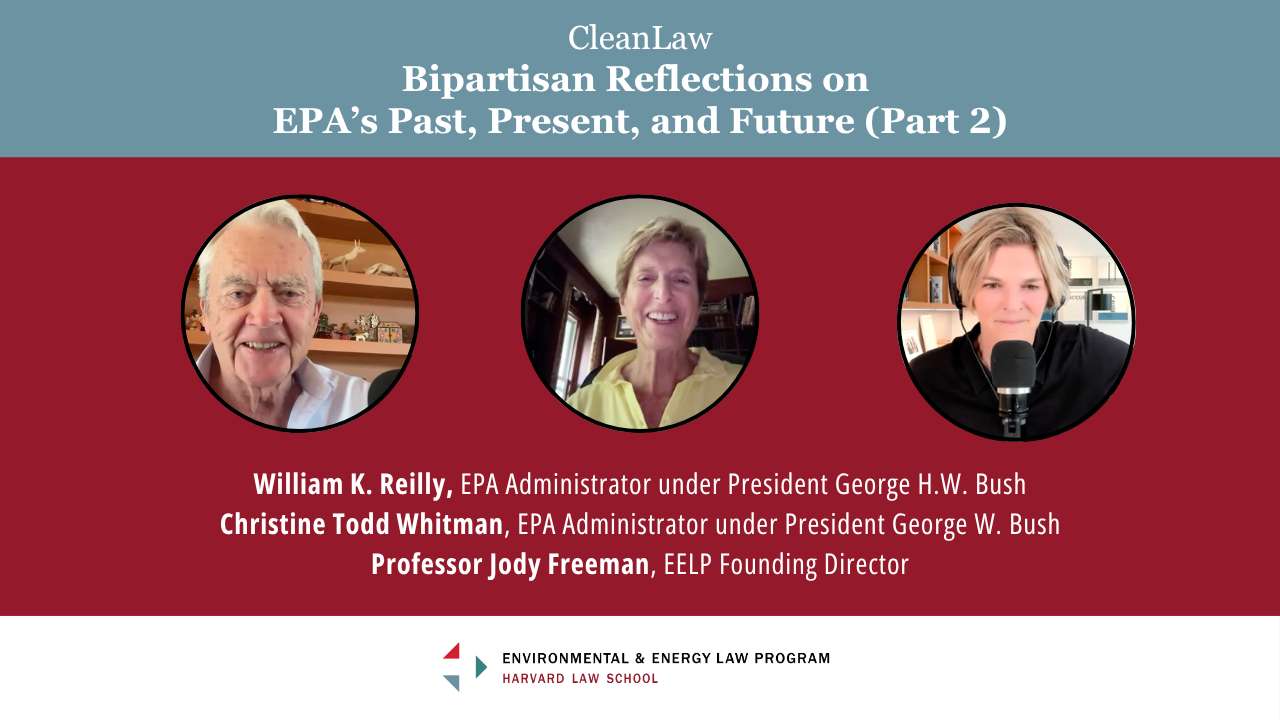

In the second of this two-part series, EELP’s Founding Director and Harvard Law Professor Jody Freeman speaks with William Reilly, EPA Administrator under President George H.W. Bush, and Christine Todd Whitman, EPA Administrator under President George W. Bush. They discuss their time at EPA including efforts to simultaneously advance environmental protections and economic growth. They also discussed the consequences of current changes to the agency under the Trump administration, including the loss of scientific expertise, and they highlight current career opportunities for people dedicated to public service.

In part I of this series, Jody speaks with Gina McCarthy, EPA Administrator under President Obama.

Transcript

Intro:

Welcome to CleanLaw from the Environmental and Energy Law Program at Harvard Law School. In the second of this two-part series, EELP’s Founding Director and Harvard Law Professor Jody Freeman speaks with William Reilly, EPA Administrator under President George H.W. Bush, and Christine Todd Whitman, EPA Administrator under President George W. Bush. They discuss their time at EPA, including efforts to simultaneously advance environmental protections and economic growth. They also discussed the consequences of current changes to the agency under the Trump administration, including the loss of scientific expertise, and they highlight current career opportunities for people dedicated to public service. We hope you enjoy this podcast.

Jody Freeman:

Welcome to CleanLaw. We have a special episode today with two former EPA administrators, Bill Reilly and Christine Todd Whitman. I am delighted to have them on the show today. We’re going to talk about the Environmental Protection Agency, their tenures leading it, and also talk a little bit about what’s happening now in the current administration. This is going to be a fantastic discussion. Welcome Bill. Welcome Christy.

Bill Reilly:

Thank you, Jody.

Christine Todd Whitman:

Thank you, Jody.

Jody Freeman:

I’m so delighted that you’re here, both of you. I know so much about you and have admired you for a very long time. So I want to begin by asking each of you to talk a little bit about your time leading EPA. It was a very different era and I just wonder with some distance and some time away how you think about your tenure there. Was it something you look back on and think “I accomplished a great deal. I’m very proud of that time,” or do you have concerns about the agency and wish you had done things differently? Reflect a little bit about your experience. Bill, I’ll ask you to go first.

Bill Reilly:

Well, in looking at my tenure and the tenure of people I knew very well who were actually mentors of mine, Bill Ruckelshaus and Russell Train, what you want if you are running a complex demanding agency like the Environmental Protection Agency is a president who smiles on your agency. I had that. George H.W. Bush from the outset supported a new Clean Air Act and within about six months, we had drafted, prepared, submitted that to the Congress, and after more than a year with a good bit of contention in the Congress, it passed. It was hugely successful, both from a point of view of eliminating acid rain as a major priority and as a cost-effective venture. It cost vastly less than even we who initiated it, expected that it would. That got us off to a very good start.

I think about some of my other initiatives, the Initiative for Environmental Justice, we called it environmental equity. It’s difficult for me to talk about that now. I’m very proud of it. I think it was needed to recognize the disproportionate pollution impact of moderate income people, poor people, minorities, but it has been eliminated by the present administration. They’re proved not to be quite as lasting as we had hoped. The vital role in communications is something that I’ve often reflected on. I had a series of voluntary initiatives, that is, things that we proposed that industry, individuals, consumers do, but I had no regulatory power to effect. One of those was Energy Star and the basis for it was that it was that at the moment when computers were taking off in the American economy and they were using significant amounts of energy, and so we made a deal with one computer company to have this program Energy Star, which would recognize that they were highly efficient relative to others.

Well, before we were able to go public with it, I got a call from the Trade Association for the computers and technical companies asking if several more could come into it, and they did. Well, that was so popular with the industry and with consumers that it caused us to move further and we’ve created Energy Star for real estate and for appliances, and it turned out to be hugely successful. It reduced billions of tons of energy that were used. It has been mistaken by the current administration as a climate initiative. It never was that. On that basis, it’s now been eliminated, but it never was that. It was about cost saving and reducing energy and the associated pollution with it. Green Lights, our promotion of LEDs, Energy Star became a marketing device for the real estate industry, which was very supportive of it, and given that the president comes from the real estate industry, I was surprised that it was ended.

Those are the kinds of things I think that really mattered. The last thing that I did, and it was based on four years of research, was to declare side stream smoke a Class A carcinogen. Well, within one year, 450 communities in the United States had banned smoking from their public buildings. We didn’t have power to effect that. That’s not in the Clean Air Act, interior air. It’s strictly based upon the fact that the country trusted the agency and it trusted the government and its explanation of science and it turned out, I think, to be as powerful as anything we did.

Jody Freeman:

I want to come back to some of those highlights from your time, Bill, but first, let me ask, Christy, what you think about when you think about your tenure at EPA. You came of course from being a very successful governor into the agency and that must have affected your approach, but I’m curious about your reflection on those years.

Christine Todd Whitman:

Well, I didn’t exactly have the same support from the administration as Bill did. Actually when I first met with the president and he was asking me to consider the position, we were in the same place. I mean, he wanted not just no net loss of wetlands, he wanted more wetlands. He had actually, as a governor, put a cap on carbon and he’d had it as part of his platform when he was running for president. So I thought we were in a pretty good place. Unfortunately, the vice president didn’t share that, and so that’s what became difficult at the very beginning. That was when California had been having rolling brownouts and everyone was afraid there were going to be major blackouts in California. So the president stood up the Energy Commission and the vice president chaired it, energy task force, and I was on it. And from the very first day, they were clearly trying to take the regulation of the Clean Air Act from the agency.

They were blaming it all on EPA. They said, “It’s all EPA’s fault. That’s why the utilities haven’t gone forward and brought on new power and that’s why things are going sideways.” And so my response was, “Well, give me the proposals. Tell me where these things are. Show me where there’s utility that has a proposal for expansion and I’ll make sure it gets to the top of the list. We’ll go through it. It still has to have all the bills and whistles and hoops it has to go through, but I’ll make sure it gets done.” And they didn’t come forward with any one of them because it wasn’t an environmental issue that was stopping it. It wasn’t environmental regulations. It was economics. The utilities didn’t think that they needed it or that it made sense to them, their bottom line, to bring on more energy.

So that was really frustrating and that was the start of it. And followed soon thereafter by my first trip overseas to the G7, I guess it was the G8 or G7 and environmental ministers. I had cleared this up and down the White House to say, “Look, I know we’re not going to endorse the Kyoto Protocol.” That was no surprise. Bill Clinton hadn’t even tried to get it through the Congress because there was no appetite on either side of the aisle for it, the way it was structured at the time. But since the president called for a cap on carbons, I said, “I want to be able to say that we’re going to put a cap on carbon.” Everybody was fine, all good. I go over, I say that we’re not going to sign the Protocol, with no surprise to them, but we will put a cap on carbon.

I get back, and unfortunately there were those in the Senate, particularly Republicans who thought I was trying to undercut the administration. It was a back door to signing Kyoto. They raised heck with the administration, and I got these rumors after I got back that in fact, we weren’t going to regulate carbon. So I went over to the White House to say, “What’s happening and why would we not? And there were ways to get it to look good.” I said, “Why don’t we take all the things that have been done by voluntarily? Because a lot had been done by companies voluntarily to reduce their emissions.” And I said, “Call out a win so we could look as if we’re moving forward, then we can move forward.”

But it wasn’t good enough. And so there was a letter. The vice president got the president to sign the letter. It was sent out to the Hill that not only we were not going to sign the Protocol, we were not going to put a cap on carbon, which was a little embarrassing. I had to call my cohorts around the world and say, “You know that thing I told you we were going to do? Well, we’re not going to do it.”

But there were several good wins that we had. For instance, the watershed-based management program we instituted for water pollution, meaning that we could help utilities ensure that they were delivering clean drinking water. What we said was, “That’s all I care about.” If they were able to do it by negotiating with the polluters upstream to change their behavior so that the water utilities didn’t have to put in hugely expensive new equipment and therefore raise the rates on their ratepayers, great, as long as the consumers were getting clean, safe drinking water. We were also able to reduce the emissions from non-road diesel engines, which are backhoes, tractors, and things, which interestingly enough, I was told by the scientists were more polluting than their on-road brothers, the trucks and things.

And so we started to move forward with that. I was told I couldn’t do it. I would destroy the engine manufacturing in various districts. Congressman told me that what I did was going to be really bad, so I put together a group. I brought an engine manufacturer who was willing to talk about this. The Office of Management and Budget, OMB, which most people don’t recognize actually runs the government because no matter how well you think you know your agency or how you want to spend your money, they tell you what you can do or not. I put in EPA scientists along with one of the major national environmental groups and I said, “Let’s work this out. This is a problem. Let’s work it out.” And they did. And they came out with a regulation that reduced those pollutants by over 95% and they were all happy. And in fact, the Natural Resource Defense Council said it was probably the best thing done for human health since removing lead from gasoline.

Of course, I love that quote. I could go to the administration and say, “See, if you just work with these people, you can get support.” But of course, the other environmental groups hated what the NRDC had done and they put a lot of pressure on them. So I subsequently got a letter from them saying, “Well, we’ve looked at the Clean Air Act and there may be other things that are better, so don’t use that phrase.” Of course, I went out and use the phrase all the time, as an example that in fact, both sides play these games. It’s not just one side that uses really important issues for political gains.

And then we did the same thing actually with air handlers and coolers. Again, it was a question, and I think Bill talked about it as one of his successes where you get one of these manufacturers to agree, yes, we can do it, whether it’s Energy Star or not, but once you get one, you start to get them all and they start to fall into place really fast, and that’s what you’re doing when you give them the ability to reduce their output and reduce their pollution. They use it as a marketing tool.

And so the air conditioners were able to use it with Energy Star and say, “This is how much more you’re going to save every year on your energy costs and how much pollution you’re going to reduce.” And people loved it. People do like it when you give them a choice that they can manage for themselves and don’t see as being overwhelming. They basically want to protect the environment. So these kinds of things were good and were successes, but I eventually left because I started losing more of the battles than I was winning.

Jody Freeman:

The two of you, your tenures were different in many ways and similar in some ways. Bill, you mentioned serving George H.W. Bush at a time when he was very strongly backing the Clean Air Act amendments that led to the cap-and-trade program to bring down sulfur dioxide and became a demonstration project for a cap-and-trade approach to pollution. You’re both Republicans who were serving Republican administrations. Christy, in the George W. Bush era, you were there at a time, different politics, didn’t have the backing of the White House, an era of kind of backlash to the climate progress that the Clinton administration had made. So you were dealing with really different political situations even though they were both Republican administrations. And I wanted to ask you both about some of those commonalities and some of those differences.

So for example, the thing in common you seem to have is this deep respect for science. You’re both deeply committed to environmental research, scientific research, and it sounds to me from your histories and from knowing what I do of you, that you respected the career staff and the work of those at the agency who supported the regulatory role the agency had and who helped give you information you needed to deal with business. Is that right that you both felt this strong support of the scientific mission of the agency? I ask it of course because that is something that’s being eroded at the moment, and I wonder if you could reflect on that, your relationship to the science, to the research, to the staff. Christy, can I ask you to go first and then I’ll ask Bill?

Christine Todd Whitman:

Absolutely. I mean, I had great respect from them and I found even though I was told when going in, “Watch out. They’re all a bunch of tree huggers who hate Republicans. They’re Democrats. They’ll just bury anything you want to do in a bottom drawer.” I found people who were just committed to the mission of the agency to protect public health and the environment. And while they might’ve wanted to do things a different way than I was proposing or the administration was proposing, as long as they felt you were really trying to improve public health and protect the environment, they’d do it. They’d work with you. And science was just incredibly important, and that’s what you have to remember. I mean, I’m not a scientist. You have to respect the knowledge and the understanding that the science brings to the table. And to see that they’ve now done away with the Office of Research and Development at EPA is just mind-boggling to me.

I mean, that’s going to set us back years and it’s going to endanger the health of the people in this country, my children and grandchildren, and it’s going to hurt the land that we love. So the open spaces and things, it’s really sad to see that go because it’s going to deny us the ability to find out what is safe and what isn’t safe. Have we reached a point where there are regulations that can be rolled back because we’ve solved a problem or is it really that bad a problem as we thought it was? Maybe. And we can find other things that, oh, by the way, this really is a problem and we hadn’t looked at it and now we need to do it, but we won’t know those things without the Office of Research and Development, without the scientists who were so committed.

Jody Freeman:

And Bill, I think I’ve read that when you went in the agency, you had a view that’s not that far from Christy’s, which was maybe these people are a little bit zealous, and what did you find?

Bill Reilly:

It was more negative than that. I came out of the environmental community and I had an experience of impatience with the failure of EPA to act on problems that had been recognized before and going through too much bureaucracy to get there. I utterly reversed that view. In fact, before I went there, as I was getting ready to go to EPA, I developed a plan to consult the Science Advisory Board and asked them, “What are the major problems facing the environment health and the ecology of the people of the United States?” And within a few months they gave me that list and at the top of the list was climate change, wetlands and related shoreline issues. Air pollution was right up there. Hazardous waste was not. And one of the problems we addressed to the extent we could was to rebalance the budget, which was two-thirds devoted to waste, hazardous waste and Superfund and get that priority better.

I can recall, though apropos of the reputation of EPA, I asked the Interior Secretary Manuel Lujan one day, “How do you like your job?” He said, “Well, I like my job great.” But he said, “The major problem is when I give an order to the Bureau of Mines, they salute and say, ‘Yes, sir,’ and it gets done. When I give an order to the Park Service or the Fish and Wildlife Service, they want to check with God first. And they stopped and he looked at me and he said, ‘Lord, I forgot who I was talking to.’ That’s all you got is people who check with God.” Well, there’s some truth to that. It has more former members of the Peace Corps than any other agency of the government. Now, you know those folks did not go into the Peace Corps to burnish their CVs or make money. I came to have huge respect for my people. They compelled it. They were so good and very loyal.

And I remember when I left, I was told by the assistant administrator, or I guess it was the top civil servant in air, he said, “One thing that you did is you never made any distinction between the politicals and the career staff.” And I said, “No, I didn’t. And if anything, I probably got more service from the latter.”

Jody Freeman:

It also sounds like not only did you have good working relationships and good respect with EPA politicals and career staff, both of you, but it also sounds like you both brought a certain pragmatism to the leadership. It’s clear from your histories that you believe, I think this is right, that if you don’t engage business in the project of environmental protection, it’ll be hard to implement even the smartest and most well-designed rules. And I think I’ve read about both of you that you have a kind of environmental protection is good for the economy philosophy, that the two are intertwined. Do I have that about right? Christy, let me ask you first.

Christine Todd Whitman:

Oh, absolutely. I mean the numbers have proven that time and time again. You show that this idea that’s a zero-sum game, that you can’t have a clean and green environment and a healthy growing economy, it’s just wrong. In fact, I would argue you can’t have one without the other. You can’t have an economy that’s thriving if people don’t have clean air to breathe and clean water to drink and places to get out to renew themselves. So that is an absolute given as far as I’m concerned. And the people at EPA, they believed that absolutely, and it was always a fight, a battle to say, “No, no, here are the facts. Here are the statistics that show you that you can do this and that you need to do this.” In fact, when Bill was actually enforcing some of the most complicated rulemaking you saw that the economy was taking off.

I mean when business were being regulated, it wasn’t hurting their bottom line. It might cost them a little bit upfront, but they became far more efficient and it was better for them. So it’s one of those things that’s always frustrating that both sides use it unfortunately to kind of pursue their aims to say that, “Well, no, you got to have one. You can’t have them both.” But that’s just wrong, and I think the younger generation is beginning to get that. Certainly, the ones I talked to are starting to see that really you’re not going to thrive if you don’t have a clean and green environment.

Jody Freeman:

Bill, you took that approach too. You already cited some of your initiatives reaching out to work with business, voluntary initiatives and so on. Can I ask you something more specific about it, which is why is this so difficult to convince people of now? Is it just that environmental issues have become more politicized and so you can’t make the argument that you can do both environmental protection and something that’s good for the economy? Why is that message really tough to get across now?

Bill Reilly:

I have been involved for some years with the Nicholas Institute for Environmental Policy Solutions at Duke University and we conducted some polling a few years ago to try to get answers to some of those questions. One of the questions was why farmers who are the first to experience and understand that the climate is changing, are opposing climate initiatives? And what came back to us was a sense that the major environmental problems the country faced back in the days when you couldn’t see across the street in Los Angeles, say, have been solved and that to go further down that road will affect jobs, will affect the economy, and it’s not something we can afford to do. That was the lesson that came back to us.

I had run a project called Business and the Environment in the private sector at the World Wildlife Fund before joining EPA, and I knew the executives who were the most responsive on the environment and I remember saying to our enforcement staff, “Look, we’ve had 18 years of experience. We know who the good guys are and we know who the problems are. Let’s concentrate on the latter and if there are initiatives and there were some, as to how we could more efficiently or cost-effectively administer some of our regulations, let’s listen to them.” And we did. I think that got a lot of support from them.

Christine Todd Whitman:

I always said that business deserved to be heard on a regulation that they needed to be part of an advisory panel when it was a regulation that was going to affect their interests because frankly, they knew more about that industry than anybody else and they could give you a better sense of whether a certain approach will work or not or how expensive it’s going to be. They shouldn’t be the majority party on an advisory panel, but they have a right to be heard, because they were going to know more about it than anybody else on how to implement it and what it really would cost and how difficult it might or might not be to put together.

Probably my best example is when we finally got an agreement to clean up the Hudson River. We designed an in-house way to do it. And I said, at the time, “This is great. We’re going to implement this agreement, but I want us to go back in six months to make sure what we’re doing is working.” The environmentalists all said, “Well, this is just a cop-out and a way of GE to get around their responsibilities and everything.” But when we went back and looked, it turned out that what looked good in the lab and we hadn’t listened to business, didn’t work out as well as it should have, and in fact, we found we were releasing more pollutants, so we had to go back and redesign and we did it and now the river is fishable and swimmable and improved greatly.

Jody Freeman:

Both of you have also dealt with a party that was changing beneath your feet. Christy, you wrote a book in the mid-2000s called It’s My Party Too, which I hope I’m accurate in saying, was an argument against a kind of social fundamentalism that you thought was overtaking your party, sort of social zealotry if you will, that you thought was adding to a climate of partisanship. And I wonder how you think about it now just about 10 years later.

Christine Todd Whitman:

Well, I certainly have to change the title. We wouldn’t go with it, It’s My Party Too. I mean, frankly in something like this, there’s no satisfaction in “I told you so,” but what I was calling out in the book was exactly what’s happening now, only taken to a degree I could never have imagined, the fact that Donald Trump was ever elected president much less twice was incomprehensible to me. Having had interactions say with him here in New Jersey while I was governor, I knew what kind of a person he was. I knew some of his capabilities or lack thereof, but I always felt that it was interesting that his casinos lost money. I’m not sure how a casino loses money because they control it all and his were the only two in Atlantic City to lose money at the time, but I never could have imagined we would be where we are here today.

Jody Freeman:

Well, I took comfort from your book because I’m a sort of radical moderate myself. I have a lot of empathy and sympathy for progressivism, but also for the argument that business needs to be part of the solution, and so that seems increasingly rare. Bill, I think you agree with this philosophy that there needs to be a kind of return away from partisanship toward common ground on environmental issues and sustainability and climate change, and I wonder how you think about that now. It seems so far away, the old days, 40, 50 years ago when Republicans and Democrats both voted for environmental protection, voted for the landmark statutes together. All those original bills in the 1970s and 80s were bipartisan bills. The National Environmental Policy Act, right, Bill, the landmark statute about look before you leap and take account of environmental harms before you take major federal action and build things, or the fundamental statutes like the Clean Air Act, Clean Water Act. They were all wildly bipartisan.

And many of these bills were signed by Republican presidents, and so Christy just spoke to the changing party, but Bill, how do you think about how far we are from those days when both Democrats and Republicans voted together for some measure of land protection, natural resource protection and environmental protection?

Bill Reilly:

We had very reactionary forces at work during my time at EPA. We’ve always had them in the country. I used to distinguish between business executives who read Forbes versus those who read Fortune and the latter actually were trying to understand the changes in the culture and respond to them while the former was resisting them and encouraged business to. In the late 80s, the president’s pollster who was to become the president, George H.W. Bush’s pollster, Pete Teeter did an analysis that concluded that the environment had entered the DNA of the American public. That is to say somewhere in the mid-80% supported strong air and water laws and a good portion of them wanted them strengthened. That, I don’t think would be different today. I suspect the public still feels that way and that’s why it’s odd to me and we’re seeing it with respect to so many things.

The wholesale deportations are not actually popular in their country and we have been taken on a ride in a sense in a very different direction and the party has gone along with it. It’s a mystery how long this can last. There’s reasons for why they have gone that direction, a very successful and imaginative campaign to create doubt about the scientific validity of climate analysis for example, and that may be something that a large proportion of the public supports, of course, whether they do or not, when they vote for someone who considers climate a hoax and they vote that person president, they’ve made pretty clear what their priorities are. We are living in a time that is, I think, going to change. I believe that the best investment anybody can make in the next few years is to begin to craft the structure of rebuild agencies.

Now, some of our agencies need reform, and I’m highly sympathetic, especially after I saw the failure of the Biden administration to get the money out the door within an appreciable period of time because of six months necessity to review them over at Christy’s favorite agency, the Office of Management and Budget. There’s a lot that needs doing to improve these agencies. EPA was created largely with a strong sense of politics. NOAA should have been a part of it, the oceans enterprise. It wasn’t because, well, it had originally been intended to go to the Interior Department and turned out the Interior secretary attacked the Vietnam War policy, so he didn’t get NOAA and NOAA went to of all places the Commerce Department where Commerce secretaries who are invariably trade experts have scarcely known what to do with it much of the time.

We have a lot that we can consider now with an eye toward more efficiency, more effective collaboration with all the elements in society, more specific regard for science. I think all of those things can be done in the years ahead and be prepared when the time comes, as I think it will, to go back and reconsider the enterprise that is now being destroyed.

Jody Freeman:

Well, let me ask you, Christy, about this because let’s turn now squarely to what’s going on in the current administration with respect to EPA and with respect to climate and environmental policy. There’s a wholesale undoing and unraveling of the legacy of President Biden and President Obama, both who had made real progress establishing the first federal rules to regulate greenhouse gas emissions in the US economy under the Clean Air Act, and all of those regulations for cars and trucks for the power sector being not just rolled back but eliminated, and the administration going so far, I think coming shortly, will be a decision to rescind the endangerment finding for greenhouse gases to say that that endangerment finding should never have been made and isn’t legal and therefore the legal predicate for regulating greenhouse gases in this country no longer exists. If my prediction is right, it basically knocks out the Clean Air Act as a source to regulate.

And if Congress is going to take itself out of the game on climate as well, which we just saw with the Big Beautiful Bill, rescinding the investments, the tax credits that Biden administration had pursued in their budget bill, right, the Inflation Reduction Act. If all those incentives and investments are being rolled back, you no longer are using a kind of industrial policy approach, and if you don’t have regulation of greenhouse gases and you don’t have investment as the alternative and you don’t have a cap-and-trade scheme, which of course you referred to, Christy, with the Kyoto Protocol trying that internationally and so on. If you have none of these levers, then you’re back at square one on a very important global issue. How do you think about that as you watch this happening?

Christine Todd Whitman:

Well, I’m discouraged. I guess that’s the first thing. You’re rolling back things that Richard Nixon put in place. This should be a Republican issue and Republicans should embrace the environment. It’s hard to get the public to understand things like carbon emissions. Those are just not something they think about every day. But I do believe we’re going to start to see some pushback from these rollbacks of protections that have been enacted over the years, particularly when you have things like floods and the kinds of disasters we’ve seen in Texas and around the country. When people see the weather changing and it starts to impact them, they’re beginning to connect the dots and when they hear that the administration is doing away with NOAA, was doing away with a scientific exploration of where the worst flooding is going to be, they were outraged. They hit back and that was taken off.

They stopped that because there was an outcry that said, “No, we have to consider climate change as we’re mapping future flood zones.” But I do believe that the public is going to start to become more invested in ensuring that there are protections because it takes a long time to understand the impact of emissions on endangerment, and poor communities where kids are getting asthma and having terrible problems with their health, and people are having problems with their health because of pollution, but that takes time, time to develop so that they connect the dots. That’s our responsibility as a country. We don’t seem to respond unless it’s some kind of a major problem, and then we respond really well. I just hope we don’t have to have a worse disaster than the kinds we’ve been seeing.

And I do believe that the public is starting to put together some of these things and say, “Well, maybe environmental protection isn’t totally bad,” even if they don’t understand exactly what happens when ORD is done away with and they might not understand the nuances of when the environmental protection has gone away and so many of the regulations have gone. For many of them, that’s the organization that either requires them to spend more money or to change the way they behave with no visible advantage to them. If you tell a farmer, “You got to change the way you handle your manure. You can’t dump it next to the stream,” and they’ll look at you and say, “Well, great, but I can’t afford to change that, and if I were to make that investment, that would cut out the kind of investment I could make to grow my crops and that’s my livelihood.” So it’s difficult, but I do believe we’re starting to see change.

Jody Freeman:

I think to myself when you say that, Christy, about you need to see sort of disasters and catastrophes, I mean, how many do you need? The terrible Lahaina fires in Hawaii, the LA fires. I mean, we could go on, the terrible hurricanes, flash floods, that all have some relationship to a climate that’s becoming more erratic and events becoming more extreme. Something you said also puts me in mind is something Bill Reilly once said to me, which is “Nobody likes EPA because EPA is the agency that’s in everybody’s shorts. It’s telling them what to do.” Could you talk a little bit, Bill, about what do you do to be a good communicator about the value that an agency like EPA brings to the society?

Bill Reilly:

Well, to tell the truth, I am more concerned about the loss of scientific research capabilities and the destruction of the science agencies and the lead that we have in so much venturesome science than I am about the environment. I suspect the environment, I’ve thought this for a long time, is going to take care of itself in the sense that as soon as we see the first river catch fire or as soon as we see the first debacle of incapacity to manage a hurricane and the floods associated with it, I think the public, as Christy implied, are going to begin to reconsider what has been done. But I don’t see any way to reconstruct the science. People are not going to march for science, and that worries me much more, to lose our lead in science, to lose some of the marvelous projects that I’m familiar with, particularly several at Yale that we really want answers to questions and we’re not that far from them, but now we are because they’re stopped. That, I think, is a calamity.

Jody Freeman:

Yeah, it’s interesting when you say the environment will take care of itself, I’m just very worried that people are becoming inured to bad things happening and things like toxic standards and air quality standards sound very abstract and they sound very remote, but you need to have them, don’t you, as a baseline?

Bill Reilly:

Jody, don’t get me wrong, I was predicting that the incidence of disasters and calamitous consequences of bad environmental policies, I was predicting that with Bill Ruckelshaus during the first Trump administration. I have a very poor record of anticipating the public’s patience with the current situation.

Jody Freeman:

Yeah.

Christine Todd Whitman:

Yeah. You’re not the only one. Believe me. You shake your head when you see some of these things going on say, “Come on, people, don’t you get it?” And people who don’t believe in climate change, don’t believe in regulation, you want to say, “Okay, there are fires up in Canada. You have smoke problems in the northern states, even down in New York City, you get the smoke, so that means it doesn’t stay in Canada. That means there’s transport, it moves. So that’s why you have to have national regulations for some of these things. What’s safe to drink in one state, has got to be safe to drink in the other, and if you’re along the Mississippi River, guess what? It’s all part of the same watershed and that’s where you’re getting things.”

So I agree with Bill entirely about the loss of science and I’m afraid it’s not coming back. A lot of those scientists are being attracted to Europe where they’re opening their door saying, “Come on. We’ll take you. We want you.” And a lot of those scientists who have left have the institutional knowledge to really build for the next generation, but we’re not going to get that back easily. It’s going to take quite a while to build back to that level that we’ve had because they’re not going to be attracted back. It’s too unpredictable here.

Jody Freeman:

Yeah, it’s interesting because I wonder if we won’t see all these consequences till we’re very far down the road of no return, which I think both of you are suggesting might happen. Let me ask another question about something you said, Christy, years ago. You were very prescient about many things and here’s two that you were prescient about in some of your earlier speeches in the mid-2000s, and in the book again, you talked about we don’t have a national energy policy. And I remember going into the Obama administration myself and actually having conversation one day with Ron Klain and I said, “I’m very frustrated. I was working in the climate office, the new climate office that Obama had created in the White House,” and I said, “Where’s our national energy policy?”

We had this whole conversation about it. But you had said right around that time you were making a speech and you said, “We don’t have a national energy policy.” We still don’t really have a national energy policy. The question is, how do you map out a transition to cleaner energy that could be politically acceptable? This is a really hard problem and I’m thinking about it and I wonder if you guys have thought about how you might begin patching together a coalition that could support some common sense steps toward this transitional plan in a way that would be more durable, I guess, than what we’ve seen come and go where we make some progress and we roll back, we make some progress and roll back. Christy, can I ask you first for any thoughts you might have on that?

Christine Todd Whitman:

Well, the good news is there are a number of organizations that are trying to do that, people who are concerned about the environment. Businesses have already gone down the road to reduce their emissions and to be more efficient and to reduce their energy usage, to reduce their water usage, their carbon footprint, because it was good policy and it was saving them money. So that’s the voluntary side that’s been going on, and I think that what we’re going to have to build on rather than the regulatory side. It’s going to be much harder to do because you’ve got to understand right now we are so politicized that every issue is looked at through a partisan political prism rather than the policy prism, and people don’t want to solve these problems because they want to use them to excite their base. Both sides do this, and unfortunately it just confuses people.

They don’t know who’s telling the truth. They both say, “This is terrible,” for entirely different reasons, or some people say, “This is the only answer,” and other people say, “We’ll all die if you regulate this.” We have to come to a point where we can step back from the partisan politics of today, which is much worse than when I was in office. But we’ve never had a president who so seemingly doesn’t respect the constitution or the rule of law and has been able to stoke an attitude toward government that it doesn’t work, that you can’t trust government, you can’t trust the news, you can’t trust law enforcement, you can’t trust the courts. It’s going to be very hard to get people to find where that niche is where we can start to rebuild something that they can rely on.

Jody Freeman:

Bill, any thinking you’ve been doing on possibilities for building coalition on a clean energy transition?

Bill Reilly:

I think that environmentalists, and myself included, probably made too much of the transformative challenges of moving to a greener energy economy and that may have delayed somewhat the acceptance of it by the public. So many of the polling data that I’ve seen show people saying things like, “Well, I certainly don’t want the lights to go out,” or “I certainly don’t want to get cold in wintertime.” And there was never an issue like that or there shouldn’t have been. The fact is that electric vehicles, small new-scale nuclear plants, solar, wind. I had a conversation last January that’s probably moot now with Elon Musk and he said, “You ought to be reassured because these forces of energy transformation are unstoppable. They are now demonstrated and they are cost-effective, which they didn’t use to be.” Well, it doesn’t seem to matter to the administration. The administration is really flying against the current on this that it doesn’t seem to make that much difference. The technologies are undesirable because they’re not going to favor what is seen as America’s major advantage, and that’s its fossil fuel capability.

It seems to me over time, the renewable experience, particularly the Chinese experience, will force a recognition, because Europeans will pick up on it too and they already are, that we are falling behind the curve. I think that will bother Americans. It will be undeniably true and at the same time the climate will be getting worse, the fires will be getting greater, the storms will be having more impact. So I think it might be a better climate for communicating the kinds of things that would go into an energy policy. You think about areas where we don’t have policy, its often struck me we don’t have a policy for the oceans. We really don’t. And one of the great things about the environmental history of the United States is virtually every single issue we have identified as a national priority, we have made significant progress on. Air, water, and the rest. We can do that again.

And I like to think that we will. I think that as elections gradually bring more proponents of renewables to positions of congressional power and influence, there will be accommodations made that have not been made now. The states are in a very strong position to do some things without federal support. One of the lessons I got that encouraged me some years ago was a young woman from Kentucky, and I forget the office she held, but she said, “Until we were forced to, we never took much initiative on a number of environmental issues including climate.” She said, “When we were forced to and it was clear that the government was no longer going to engage in that process, all of a sudden it energized us.”

And she went through the list of things that had happened in Kentucky as a consequence of their deciding to take more responsibility on their own and then to serve as an exemplar for some of the surrounding states. I believe we’re going to see those phenomena again. There’s such a vacuum right now in terms of energetic priority setting of the sort that we’re talking about that it will feed on itself and I’m confident that it will begin to have an impact.

Jody Freeman:

Well, there’s certainly space for state leadership, and Christy, you were involved. I mean, your state, part of the Regional Greenhouse Gas Initiative that the Northeast has demonstrated that states can get together in a coalition and improve the reliability of their electricity sector and cut their carbon emissions and generate revenue all at the same time. So there are these examples of state leadership to build on.

Christine Todd Whitman:

That to me is a critical point because I think where we are going to find progress made is at the state level. I mean they always have the saying they’re the laboratories of democracies. Well, frankly they are. It doesn’t matter when you’re in government, if you’re a Republican or a Democrat, you are responsible to your people. They know who you are, they know where you are, and you have to deliver for them. And it’s on issues like this, when you share, I mean you have the Western governors are together working on lowering emissions as well as the Northeastern governors, things get done. And that can help create the atmosphere that might allow, sometime in the future, for a national energy policy, but it’s going to be the cities. You can’t forget the cities either in the towns. Mayors are individually taking up action to feed their population, to reduce pollution in their cities. A lot is happening at the state and local level. That’s where I think we’re going to see the most immediate progress made, and hopefully that will then translate on the national level.

Jody Freeman:

Well, this brings me to my last big picture question and then I’ll ask you a couple smaller personal ones and I’ll let you go. But the big picture question is take us to the international level for a moment. Both of you during your times leading EPA and in your other work have been very much a part of the development of international policy, and you talked, Christy, about when you went to the G7, I think it was then the G7, and you talked about what the US would do. Bill, you were part of strengthening the Montreal Protocol. You also were part of the UNFCCC negotiations to establish the first global agreement that at least noted the effect of climate global warming. So you’re connected to the international community and how do you think about the US’s role now, now that President Trump withdrew the United States again for the second time from the Paris Agreement? Do you think we get back to a place of leadership? Will the international community go on without us? How do you see it? Bill, I’ll go to you first.

Bill Reilly:

Well, I was in Germany last month and the Germans are apoplectic still about the speech that Vice President JD Vance delivered recommending that they vote for the AFD, which is a very right-wing fascist party in Germany. So our relations, our ability to influence the international environment I think are diminishing by the hour. We may win back some support. I mean, we are the United States and there are many initiatives that really don’t work without the participation with this central country on many things. I think that the Europeans will go on, the Chinese will go on. Chinese are proving increasingly effective at selling their cars in Africa and some other places, wouldn’t do badly for us to begin to allow them to produce those cars here. I don’t think that will happen, but we will have, I think, an open door to participation with international activities when we want it and when the terms that we offer are something that the Europeans can live with and others can live with. They’re not presently. So we will probably be excluded.

I know Canada is making trade agreements with the European Union now and that is in the interest of Canada, and they’re also making decisions about defense appropriation and purchasing that do not involve American companies. Well, this is really a perverse consequence of the unnecessary provocation that we’ve given to the Canadians. We’re doing things like that and they will prevent our having anything like leadership in any number of areas, but eventually, we will not necessarily return to leadership. I think that the record that we will have set will make people wary of us and they will want to trust and verify. But I think the moment will come. It’s not going to come within the next few years. We’re going to have to sit and watch the Europeans and Chinese and others simply demonstrate the effectiveness of a green economy of renewables and wish that we could do the same.

Jody Freeman:

Christy, do you think that’s right? We’re going to play catch-up in the end?

Christine Todd Whitman:

I agree a hundred percent with what Bill’s saying. We have lost so much face. We’ve lost so much credibility in the international community. I mean, part of it is because we’re all over the place. I mean, we say we’re going to do something one minute and then all of a sudden, no, no, no, we’re going to do the opposite. Nobody knows whether they can trust us, why they have a treaty with us, or any kind of a deal because they don’t know whether or not it’s going to last. At least under this administration, it’s true. That’s been our history of back and forth in the last, well, first Trump administration and now. We seem to disdain other countries.

But we are the United States. We’re huge, and as Bill said, there’s certain things that just can’t get done if we’re not a player, but we’re not going to be in the same position that we’ve been in the past, have the same influence, because other countries are saying we’re an unreliable partner and they need to do things for themselves, which is not all bad. I mean, it does need to be a bit of that. You’d want it as an independent nation, but on the other hand, it’s not great for us. We’re losing our authority and losing our influence and we’re going to have to sit this out for the next three years and see what happens.

Jody Freeman:

Let me ask you now a couple of personal things. I’ve been thinking about I want to write a book called Mentors and Nemeses or something like that. I’m really interested in who people have found to be their mentors, and I’m especially interested in people who are a little bit older, have lots of experience and accomplishment to ask them who were their mentors coming up, and then ask you about your own view of mentorship. How do you do it now yourself for others? First, let me ask you about that. Maybe I won’t ask you about your nemeses. I think I can guess who they were. Bill, let me ask you first, who were your great mentors?

Bill Reilly:

I had the good fortune as a 28, 29-year-old to work at the Council of Environmental Quality in the Nixon administration. I was the third or fourth hire, and the chairman was Russell Train, and Russ Train was a statesman. He was a very internationalist. I guess I was already an internationalist because I’d gone to school in France and Germany, but, I was, and he had a grasp of the larger questions and their implications that far exceeded his knowledge of detail, which was less important to him. That struck me as leadership, and I’ll give you an example. When I went to EPA, he said to me, “You were not involved in the campaign. You are not a political. You’re going to sit in the cabinet room and everybody else is going to wonder ‘How did he get here? How did he deserve this?’”

And he said, “You won’t have any friends.” He said, “I actually know these people.” And he referred to Darman and Sununu and the rest. He said, “You will have two advantages. One advantage you will have is the president. You’re his kind of guy.” Well, we really did. We went to five state dinners and so much private time with the president and Mrs. Bush, they could not have been better to us. And his openness to allow me to appoint my own people was very unusual. And I don’t know that anyone else had it other than maybe Baker. But secondly, Russ said, “Communicate, pay attention to the communications.” He said, “If you take communications very seriously and the press understands you and is with you,” and he said, “they will. You will be successful at that. You will have the White House exactly where you want them after a year, and that is afraid of you.”

So I absolutely followed Russ’s advice and I got called to account for it. I remember being told I was doing too much television or too much communicating, or Sununu would say, “You’re way out ahead of where we are in this administration.” And then Lee Atwater, who was the head of the party, would tell me, he said, “They’re watching what you do in the White House. You don’t use the document that has been cleared, but you’re getting away with it because you don’t have any other paper, so you’re just talking.” But he said, “Let me tell you, you have one huge fan for those interviews you’re doing on television, and that’s the president.” Well, I always made a distinction between the president and the White House, and for me, that worked.

Jody Freeman:

Christy, mentors who gave you good advice, like apparently Bill had.

Christine Todd Whitman:

Well, that’s interesting. I don’t think of anyone like that in my career particularly, and it sounds so mundane to say it, but it’s my parents. They really were the mentors. I grew up on a farm with a family that loved the outdoors. We spent a lot of time outdoors, fishing, hunting, all kinds of things. And I was always told, “Leave the place better than you found it.” I always leave anything better than when you found it. I also had the advice, “Your word is your bond, and the easiest thing in the world to lose is trust, and it’s the hardest thing to get back.” And those are the kind of life lessons that we were taught, and it made a difference to me and helped me as I went forward. So it really was them.

I mean, Tom Kane certainly gave me my first opportunity to serve the state in a statewide capacity, which helped me be in a position to run first for the Senate and then for governor. I mean, I always wanted to be governor, not grew up thinking about it, but it was something that I wanted to do as I got older and saw the problems that were facing the state.

Jody Freeman:

But what’s interesting to me, I never like to say first woman, this first woman that, but I’m going to do it anyway because you were the first woman governor. This is a very special achievement. It’s extremely hard to do. And I wonder, do you think about that as a big deal or do you just think I was just a governor like any other governor? Are you especially proud of that?

Christine Todd Whitman:

Well, Jody, what I’m proud of is I was the first person to defeat an incumbent governor in a general election since the Constitution had been rewritten in 1947.

Jody Freeman:

All right.

Christine Todd Whitman:

So the fact that I was a woman was just a fact.

Jody Freeman:

Okay, good. All right, I accept that. And then my very last question, which is a little bit selfish in the sense that I’m struggling now and working hard at being a good guide for my students at Harvard Law School. Bill, you’re an alum. You should feel something for this. The need at this moment to really support them in their interest in going into public service, whether they want to run for office or just be in the government. Many of the Harvard Law students want to go into the Department of Justice, but many are alarmed at what they see happening in the current administration in terms of what you mentioned, Christy, the undermining of the rule of law, fundamental commitment to the Constitution, things that we should take for granted, not policy differences, but the fundamentals.

And they’re worried about it, and I’m thinking about, how do I advise them, back to mentorship, how do I mentor? And I wonder, may I ask you for some words of wisdom? How do you think about making sure we do our bit for young people to ensure they’re still motivated and feel supported in wanting to go into public service? Christy, can I ask you first?

Christine Todd Whitman:

Well, that’s one of the things we’re doing with the Forward party. We set up a group in the Forward party, which is a third party that Andrew Yang and I have helped establish. And we have a whole group of young people and we say to them, “Look, this is your time. This is when we need you the most. This is about your future. You can make a difference.” It’s encouraging young people to understand that they can make a difference right now. They don’t have to wait until they’re in the business community or in a big law firm. They can start making those differences now. You should be excited about this opportunity because so much is being torn down. Now is the time to really take a stand to build up the legal community and the justice community and start to make them the kinds of organizations that can preserve our democracy. Democracy is teetering on the edge, and that’s what you need to use as your incentive to go forward and get through law school.

Jody Freeman:

Bill, I’ll give you the last word on this.

Bill Reilly:

Well, there are exceptions for national public service. I have served in the military and I’m a strong supporter of the Army and Navy. I noticed that West Point just had five Rhodes scholarships, four of them women. And I hope that this administration does not interfere with some of the successful institutions that do depend upon adherence to rules and procedures and behaviors that are longstanding and largely observed. The other side of public service, I’ve given lectures lately at Yale and at Duke, and I was struck by how exuberant people were and how confident they were. I expected a different attitude.

Now these were undergraduates, but it was very energizing for me. And one bit of advice I gave to someone who was interested in public service was skip Washington. I said, “Identify somebody at the local or state level that’s easy to identify them, the comers, the energized people, the people with ideas who are making a career and go to work for them and follow what they do.” And as they move up, you will move up and you will also learn from the bottom up how government can function honorably and with distinction, which you won’t necessarily learn in Washington.

Jody Freeman:

Well, that is a fantastic note to end on. Both of you have served honorably and with distinction, and I know you’re not done, so I want to thank you both for all that you did in your time in the federal government, but also all that you do now in your projects and work and consulting and advising and board service and everything you’re involved in. I so admire you both and so appreciate you both, both for historical reasons, but also as good examples going forward for me and for my students. So thank you for making the time. I can’t think of two more important people to have on the podcast as we watch what’s happening to the US government and to EPA in particular. So thank you so much. It was a pleasure to have both of you.

Bill Reilly:

Thank you, Jody. Very good interview.

Christine Todd Whitman:

Thank you, Jody, for caring.