*Updated on Feb. 1, 2023

For more on the phase-out of SEPs at DOJ and EPA under President Trump, see DOJ Phases Out Supplemental Environmental Projects in Environmental Enforcement and EPA Changes its Settlement Practices.

For decades, the Department of Justice (DOJ) and the Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) have relied on the discretionary use of supplemental environmental projects (SEPs) in settlement agreements to redress the impacts of environmental violations on communities. Unlike civil penalties, which go to the US Treasury, SEPs allow companies to voluntarily support projects that can provide important health benefits to impacted communities, including investments in enhanced monitoring or remediating the effects of illegal emissions or discharges.

EPA’s SEPs policy, last updated in 2015, applies to administrative enforcement actions. Prior to the Trump administration, DOJ had not issued a rule addressing third-party payments, but DOJ’s Office of Legal Counsel (OLC) had upheld the use of certain third-party payments, including SEPs, in civil environmental actions. Under President Trump, DOJ abruptly reversed course and phased out the use of SEPs and other third-party payments through internal guidance and a rule finalized in December 2020. On May 5, 2022, Attorney General Garland issued a memo and an interim final rule, published on May 10, 2022, that restored DOJ’s authority to enter into SEPs and other third-party payments in nearly all federal civil and criminal cases, subject to new guidelines and limitations.

That same day, the Biden DOJ also announced two significant environmental justice (EJ) initiatives: the opening of an Office of Environmental Justice within the Environment and Natural Resources Division (ENRD), and a new “comprehensive environmental justice enforcement strategy” co-developed by ENRD and EPA. Both initiatives respond to mandates in Biden’s executive order 14008, which also required DOJ to “ensure comprehensive attention to environmental justice” throughout the department. According to DOJ’s interim final rule, reviving the use of SEPs in particular helps to “remedy[] the harms to communities most directly impacted by violations of [environmental] laws.” While DOJ’s new policy does not include explicit EJ provisions, EPA’s SEPs policy includes guidance prioritizing approval of SEPs that advance EJ concerns and integrate community input.

In this blog, I review the history of SEPs in federal environmental enforcement, respond to legal arguments made by the Trump DOJ alleging that SEPs and other third party-payments violate federal law, and compare DOJ’s and EPA’s policies.

Background: SEPs in Federal Environmental Enforcement

EPA defines SEPs as “projects included as part of an enforcement settlement that provide a tangible environmental or public health benefit.” SEPs are voluntary, and EPA cannot require or compel a defendant to perform a SEP. Furthermore, SEPs are projects that “are not otherwise legally required . . . and thus provide benefits that go beyond compliance obligations.” For example, in 2006, EPA reached a settlement with the University of Puerto Rico at Mayagüez to address self-reported violations involving hazardous waste, discharge into waterways, and emission of hazardous air pollutants. Under the final agreement, the University committed to spend almost $400,000 to set up an environmental management system to properly store, handle, and dispose of hazardous materials used on campus, in addition to paying $100,000 in civil penalties. The University also committed to share its experience with other federal, Commonwealth, and municipal agencies to prevent similar violations. The SEP thus allowed the University to invest in a long-term solution to clean up the contamination and prevent future discharges, in addition to paying a civil penalty to the US Treasury.

Because SEPs are projects that could not be otherwise ordered by a court, they are distinct from injunctive relief, including mitigation. According to a 2012 EPA memo, there are three key differences between SEPs and mitigation: (1) the legal basis for each, (2) the nexus to the underlying violation, and (3) the impacts on the size of civil penalties. Mitigation is relief a court could order to “restore the status quo ante,” and, therefore, has a direct connection to the past or ongoing harm from the violation. SEPs are voluntary and can have a less direct tie to the violation itself. Under EPA’s SEPs policy, SEPs may also lead to a reduction in civil penalties.

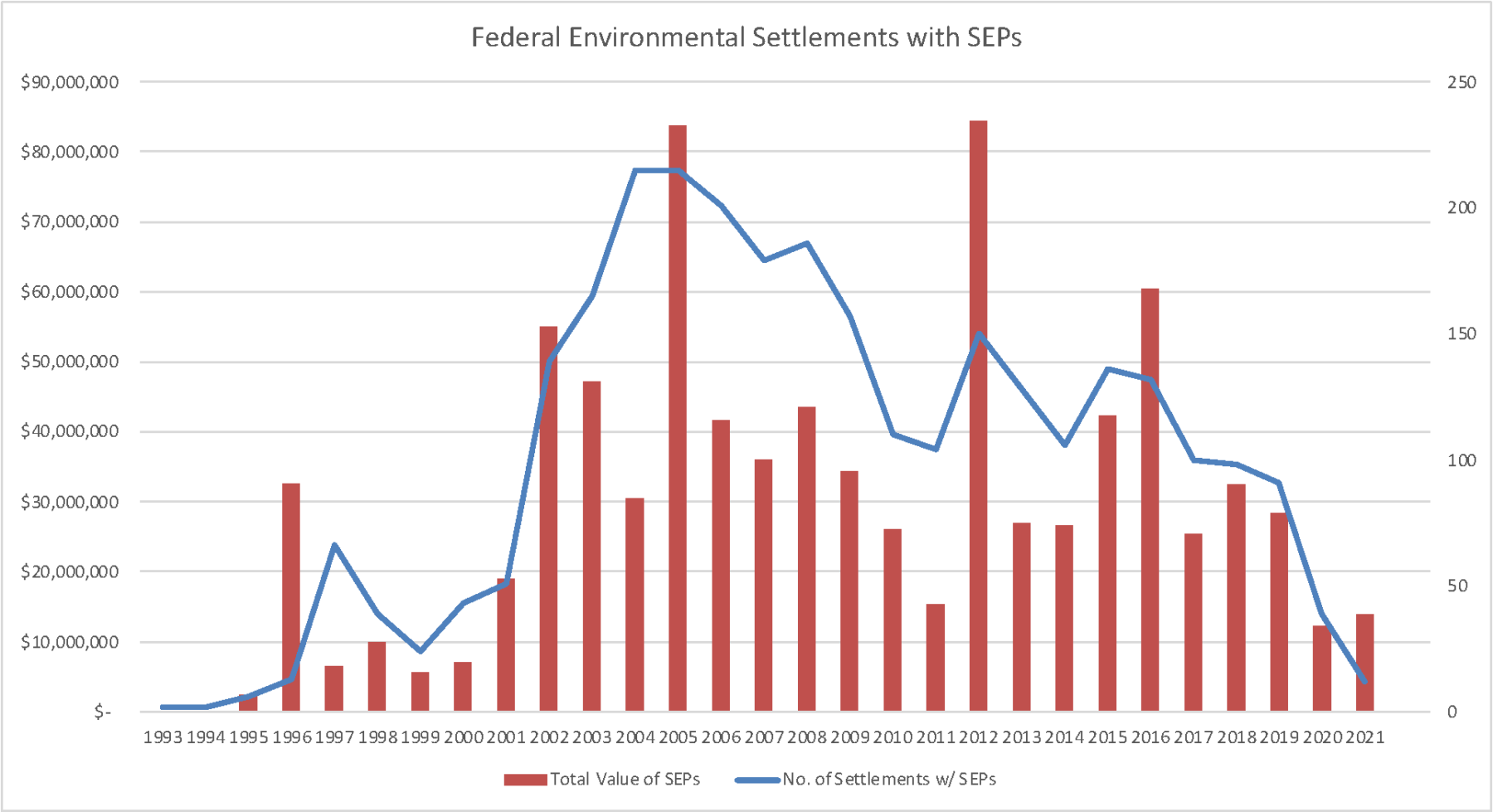

According to EPA’s Enforcement and Compliance History Online (ECHO) database, since 1993, nearly 2,800 federal environmental settlements have included a SEP. The chart below shows the total value of those SEPs per year compared to the annual number of federal environmental settlements with SEPs.

Data Source: EPA’s ECHO Database

Starting in 2017 under the Trump administration,[1] DOJ issued a series of policy memos to curtail the agency’s authority to include SEPs in settlement agreements, cementing the approach in a March 2020 memo and final rule published on December 16, 2020. The Trump administration’s final rule prohibited any settlement agreement “that directs or provides for a payment or loan to any non-governmental person or entity that is not a party to the dispute”, with four narrow exceptions. In the March memo, Trump officials argued that SEPs in particular exceed agencies’ budgetary authority stating “in-kind payments in exchange for a reduction of a penalty are as problematic as direct cash payments to third parties.” EPA did not revise its SEPs policy, instead relying on agency discretion to halt the use of SEPs in administrative settlements consistent with DOJ policy.

The March 2020 memo and December 2020 rule replaced earlier guidance from the Trump administration—a January 2018 guidance memo from then acting Assistant Attorney General for ENRD Jeffrey H. Wood—that would have allowed ENRD to use SEPs where payments “directly remedy harm to the environment” and are in proportion to the harm that occurred. For example, in a Clean Air Act case involving a stationary source, the 2018 guidance would allow a “lawful payment” addressing harm from excess sulfur dioxide emissions within the same airshed as the source. Thus, the Trump DOJ did allow SEPs in environmental settlements until March 2020, albeit under limited circumstances.

For more, see DOJ Phases Out Supplemental Environmental Projects in Environmental Enforcement.

President Biden identified the Trump 2020 rule as a priority for review under executive order 13990, and DOJ revoked the March 2020 memo prohibiting the use of SEPs on February 4, 2022. Because EPA never revised its SEPs policy but rather relied on internal guidance to limit the use of SEPs, the agency could immediately resume including SEPs in administrative enforcement. However, because the Trump DOJ finalized its SEPs prohibition in a rulemaking, the Biden DOJ was required to revoke and replace the Trump rule to reinstate the use of SEPs in civil actions.

DOJ’s New Policy

On May 10, 2022, DOJ published an interim final rule revoking the Trump rule, effectively reviving the use of SEPs consistent with Attorney General Garland’s memo issued on May 5. The Biden rule, like the Trump rule, is internal and, therefore, exempt from notice-and-comment requirements under the Administrative Procedure Act (APA). The rule is effective immediately, but DOJ also accepted public comments.

The new rule preserves DOJ’s discretion to prescribe settlement practices through internal guidance. According to DOJ, “policies [about settlements] have traditionally been addressed through memoranda from Department leadership rather than through regulations.”[2] By returning to this tradition, the Biden DOJ enables a future administration to immediately amend the third-party payment policy through new guidance, making the policy vulnerable to reversal.

DOJ’s policy includes new restrictions limiting the scope and potential impact of third-party payments, including SEPs, and directly addresses several of the legal arguments the Trump administration had advanced (discussed below). These limitations include:

- The “nature and scope” must be defined “with particularity.”

- There must be a “strong connection to the underlying violation,” including by advancing at least one of the objectives of the underlying statute.

- DOJ will not propose the selection of a third party or specific entity to receive payments or implement a project, though DOJ can specify the type of entity. DOJ can disapprove a third party proposed by the defendant if the disapproval is based on objective criteria.

- The settlement must be executed before a ruling in favor of the US, and DOJ will not retain any post-settlement control over the funds or projects, except to ensure parties comply with the settlement agreement.

- Senior DOJ officials (deputy AG or associate AG) must approve the proposed settlement, with some exceptions.[3]

DOJ’s New Policy is Consistent with Federal Law

In the Trump 2020 rule, DOJ restricted third-party payments based on section 3302(b) of the MRA, which requires any federal official “receiving money for the Government” to deposit those funds in the Treasury “without deduction for any charge or claim.”[4] However, the Trump DOJ did not argue that the MRA bars most third-party payments. Rather, the rule restricted most third-party payments based on “the policy reflected in the [MRA]”.[5] This reading is consistent with an internal memo acquired via a Freedom of Information Act (FOIA) request, in which the Trump DOJ, speaking through its Office of Legal Counsel (OLC), affirmed that the prohibitions included in the 2020 final rule were a policy choice rather than a result compelled by statute. In the memo, Assistant Attorney General for DOJ’s OLC, Steven A. Engel, wrote to Attorney General Barr that while “the [final rule’s] prohibition on third-party payments is consistent with the policy underlying the [Miscellaneous Receipts Act] . . . the proposed Order does not reflect an interpretation of the statute itself and thus prohibits certain payments to third parties that this Office has concluded that the MRA otherwise allows.”

AAG Engel’s reading of the MRA as allowing “certain payments to third parties” is consistent with decades of OLC practice. In 1980, OLC interpreted the phrase “receiving money for the Government” under the MRA to include “the ‘constructive receipt’ of money ‘if a federal agency could have accepted possession and retains discretion to direct the use of the money’.”[6] OLC has therefore “consistently advised” that third party-payments included in settlement agreements satsify a two-step test: that (1) settlements be executed before an admission or finding of liability in favor of the US, and (2) the US does not have post-settlement control over the “disposition or management” of the funds or related projects, except to ensure parties comply with the settlement.[7]

OLC applied this two-step test in a 2006 decision, Softwood Lumber, which AAG Engel cited in his memo as evidence that the MRA allows “certain payments to third parties”. The Softwood Lumber decision addressed a trade dispute settlement between the US and Canada that directed $450 million to an escrow account to fund “meritorious initiatives in the US” including “charitable causes” in affected communities, “low-income housing and disaster relief,” and other “public-interest projects.” The fund was administered by a foundation, run by a board of directors not “subject to direction and control by any federal official.” The OLC found that “there is little basis for attributing any of the $450 million to the United States,” and even if there were, the foundation’s arrangement and transfer of the funds “would easily satisfy both of the MRA’s requirements [in the two-step test].”

The Biden DOJ’s new policy, outlined in the May 5, 2022 memo, and EPA’s 2015 SEPs policy explicitly address this two-step test and include additional safeguards to ensure compliance with the MRA. DOJ’s policy explicitly requires the settlement to be executed “before an admission or finding of liability in favor of the US,”[8] and both policies prohibit the agency from controlling or managing SEP funds or related projects. Both policies also prohibit the agencies from proposing a particular party to receive payments or implement a SEP, further limiting the agencies’ influence over the selection of a SEP project and its beneficiaries.

Reconciling DOJ’s and EPA’s Policies

EPA’s SEPs policy, last revised in 2015, differs from DOJ’s third-party payment policy in a few key ways. EPA’s policy offers specific guidance on how to prioritize EJ concerns in the creation and approval of SEPs in settlement agreements and prohibits all cash donations to third parties, whereas DOJ’s guidance allows restricted cash donations. EPA’s test for whether a SEP is sufficiently related to the underlying environmental violation is slightly more flexible than DOJ’s. EPA also generally assumes government officials have the authority to approve SEPs as part of approving the settlement agreement, whereas DOJ’s policy requires the deputy AG or associate AG to approve all settlements that include third-party payments.

EPA’s SEPs policy also provides additional guidance on how to develop SEPs that account for EJ concerns. Under the policy, “defendants are encouraged to consider SEPs in communities where there are EJ concerns” and “strongly encourages defendants to reach out to the community for SEP ideas and prefers SEPs proposals that have been developed with input from the impacted community.” The policy includes guidance on how to integrate community input in the context of ongoing settlement negotiations. It also explicitly states that in assessing proposed SEPs, EPA will prefer projects developed with “active solicitation and consideration of community input” and that “mitigate damage or reduce risk to a community that may have been disproportionately exposed to pollution.”

The table below compares key provisions of DOJ’s and EPA’s policies. Where the two policies differ, the more restrictive provision is marked by two asterisks (**). In a case where EPA’s policy is more restrictive, it is unclear from DOJ’s policy whether ENRD will reject SEPs that fail to comply with EPA’s 2015 policy. For example, if ENRD evaluates a proposed settlement agreement on behalf of EPA, it is not clear if ENRD must disapprove a SEP that includes a restricted cash donation to a third party because EPA’s policy prohibits such donations, even if DOJ could approve that donation if acting on behalf of another agency that does not have a conflicting policy. It is also important to recognize that states are not subject to DOJ’s or EPA’s policies and could, therefore, include SEPs in a parallel agreement that would not be subject to these federal restrictions. However, in that case, the defendant likely would not receive a reduced civil penalty, which EPA allows for in its SEPs policy.

Comparison of Key Provisions in DOJ’s and EPA’s SEPs Policies (more restrictive provision marked by **)

| SEP Policy Provision | DOJ (2022) | EPA (2015) |

| Project Scope | Type and scope must be defined “with particularity” | Type and scope must be “specifically described and defined” |

| Nexus to Underlying Violation | ** Project must have a “strong connection” to the underlying violation, advance at least one of the statute’s objectives, reduce the effects of the underlying violation AND reduce the likelihood of similar violations in the future | Project must have a “sufficient” nexus to the underlying violation and must advance at least one of the statute’s objectives. It must also reduce the adverse impact or overall risk of the underlying violation to public health or the environment OR reduce likelihood of similar violations in the future |

| SEP Approval | ** All SEPs must be approved by the deputy attorney general or associate attorney general | No special approval required except in certain cases (e.g., where SEPs don’t comply with EPA’s policy or include third-party compliance projects) |

| Cash Donations | Prohibits “unrestricted” cash donations to third parties with some exceptions | ** Prohibits all cash donations to third parties with some exceptions |

| Third Party Selection | Agency can specify the type of organization to receive the SEP, but cannot propose or select a particular third party to receive payments or to implement or receive SEP | |

| Third Party Disapproval | Agency can disapprove selected SEP beneficiary or implementers (e.g., contractors) based on “objective criteria” to assess qualifications and fitness | |

| Decrease in Civil Penalty | Not addressed | Inclusion of SEPs may warrant decrease in penalty based on various factors and subject to EPA discretion, but the final penalty amount cannot be lower than minimum calculated according to policy methodology[9] |

| Timing | Settlement must be executed before admission or finding of liability in favor of the US | SEP cannot begin until EPA has identified a violation (policy is for settlements only, not hearings or trial)[10] |

| Post-Settlement Control Over Funds, Projects | DOJ and client agencies have no post-settlement control over disposition or management of funds or projects carried out under the settlement | EPA cannot manage or control funds set aside for a SEP or manage or administer the SEP itself. EPA may conduct oversight to ensure the project is implemented pursuant to settlement provisions |

We will continue to track the development of this and other EJ-related policies at EPA and DOJ. For more information, visit those agencies’ pages on our Federal EJ Tracker.

[1] DOJ issued a memorandum on June 5, 2017, which barred the agency from entering into settlement agreements that include “payments to non-government, third-party organizations as a condition of settlement with the United States,” but allowed a “lawful payment or loan . . . that otherwise directly remedies the harm that is sought to be redressed, including, for example, harm to the environment.” Memorandum from Attorney General Jeff Sessions on Prohibition on Settlement Payments to Third Parties (June 5, 2017) (available at https://perma.cc/4MS6-AHYK).

[2] 87 Fed. Reg. at 27937.

[3] No approval is required for: (1) lawful payments or loans that provide restitution or compensation to a victim to directly remedy the harm being addressed; (2) in cases of foreign official corruption, payments to a trusted third party when required to facilitate the repatriation and use of funds; (3) payments for legal and other professional services rendered in connection to the case; and (4) payments expressly authorized by statute or regulation.

[4] 31 U.S.C. § 3302(b).

[5] 85 Fed. Reg. at 81410 (emphasis added).

[6] Effect of 31 U.S.C. 484 on the Settlement Authority of the Attorney General, 4B Op. O.L.C. 684, 688 (1980). In this case, OLC disapproved a proposed settlement agreement between the US, the Commonwealth of Virginia, and a trucking company for environmental damage resulting from an oil spill. The agreement included a provision requiring the company to donate money to “a waterfowl preservation organization to be designated jointly” by Virginia and the Department of the Interior. The OLC found that 31 U.S.C. § 484, the predecessor to § 3301(b) of the MRA, bars cash payments to third parties where the federal government “could have accepted possession and retains discretion to direct the use of money.”

[7] Application of the Government Corporation Control Act and the Miscellaneous Receipts Act to the Canadian Softwood Lumber Settlement Agreement, 30 Op. O.L.C. 111, 119 (2006). OLC had previously transmitted this guidance to U.S. Attorneys’ offices in 1996. See, Memorandum for the Files, from Rebecca Arbogast, Attorney-Adviser, O.L.C., Miscellaneous Receipts Act and Criminal Settlements (Nov. 18, 1996).

[8] EPA’s SEPs policy is to be used in settlements only and is “not intended for use by the EPA, defendants, courts, or administrative law judges at a hearing or in trial.” Memorandum from Assistant Administrator Cynthia Giles, Issuance of the 2015 Update to the 1998 U.S. Environmental Protection Agency Supplemental Environmental Projects Policy (Mar. 10, 2015). Therefore, EPA’s SEPs policy does not address the first prong of the MRA test that settlements must be executed before an admission or finding of liability in favor of the US.

[9] Under EPA’s policy, settlements that include SEPs must include a penalty. That penalty must equal or exceed either (a) the economic benefit of noncompliance plus 10% of the gravity-based penalty, or (b) 25% of the gravity-based penalty, whichever is greater. The gravity penalty reflects the environmental and regulatory harm caused by the violation(s).

[10] EPA’s SEPs policy is to be used in settlements only and is “not intended for use by the EPA, defendants, courts, or administrative law judges at a hearing or in trial.” Thus, the DOJ’s limitation that settlements must be executed before an admission or finding of liability does not apply to EPA’s SEPs policy.